by Max Hirsh and Pieter van der Horst

Airports own vast amounts of land. If you superimposed the average airport over a map of the city that it serves, you’d find that it’s about the same size as the entire downtown core—and many airports are much, much bigger.

Some of this land is held in reserve for future terminal and runway expansions, but a lot of it is not. The world’s leading airports view these real estate holdings as a critical source of non-aeronautical revenue. They’ve transformed that land into a variety of profitable commercial developments, including hotels, office parks, and shopping centers. Still others have built concert arenas, university campuses, and tourist attractions. But many airports hesitate to get involved in real estate projects. Why is that?

Two reasons account for their reticence. The first is a lack of ambition. Some CEOs tell me that their airports don't have any experience in real estate development, and they don't have the bandwith to develop that expertise. Their core business—getting planes in and out of the airport, and getting passengers/cargo in and out the planes—is just too complex, and too darn unpredictable. That leaves airport authorities with little time to think about anything else.

Successful airports, on the other hand, recognize that landside real estate is much more than a source of non-aeronautical revenue: it also helps to diversify income and maintain profitability during those turbulent periods when unexpected events—a terror attack, an airline bankruptcy, the introduction of new regulations and fees—lead to abrupt declines in aeronautical income.

The second reason why many airports don’t leverage one of their most valuable assets—land—is because they lack a strategic vision for their future aeronautical needs. Successful airports have mapped out the concrete next steps that are needed to grow. They’ve outlined different scenarios for future runway and terminal expansions, and identified parcels of land that will remain unaffected by those plans. That process enables them to pinpoint sites for non-aeronautical development—and to reap enormous rewards. Leading global hubs like Amsterdam Schiphol, for example, generate up to 20% of their overall income—and more than a third of their profits—through landside real estate. That’s because the profit margins on commercial developments are considerably higher compared to aeronautical charges.

Less successful airports, on the other hand, lack that kind of strategic vision. Unclear on the next steps, they hold all their land in reserve just in case some of it might be needed for future expansion projects. In so doing, they forego a massive amount of income that could be gained through landside real estate.

How can airports overcome these two obstacles? The first step is to identify parts of the airport area that are unlikely to be needed for future expansion projects. Are you really going to build a new runway at the entrance to the airport, or on land that’s right next to a heavily populated residential area? Probably not. On the other hand, these are prime locations for future commercial developments.

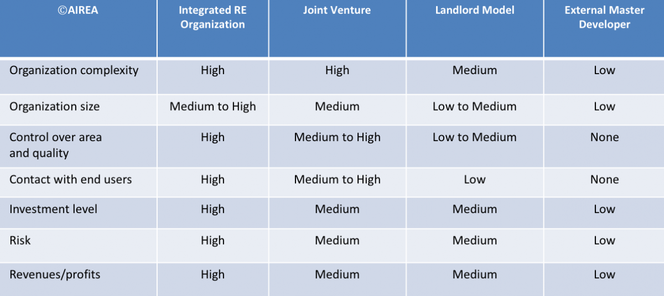

The second step is to decide which model the airport will use to develop the land. Some airport authorities have a dedicated real estate team, or form a subsidiary to manage that portfolio. In other words, they cultivate the expertise in-house, keep track of urban development trends, and maintain close contacts with the local business community to understand their evolving needs. Other airports establish joint ventures with experienced partners. For Singapore’s Project Jewel, Changi partnered with CapitaMalls, the city-state’s leading developer of shopping centers. That model allowed the airport to co-create a new space that increased retail sales, but also pushed some aeronautical functions—meet & greet, for example—into the airport forecourt. Finally, some airports take a hands-off approach, and simply sell or lease the land to third-party investors and developers. The chart below summarizes these different models.

Each approach comes with distinct advantages and disadvantages. Doing everything yourself allows the airport to maintain maximum control, but also exposes it to the most risk. Finding the right talent—people who understand both the airport business and the commercial real estate game—can also be a challenge. JVs address both of these downsides, as they allow each party to focus on their core competencies, and do what they do best. But joint ventures only work if the airport authority has the capacity to collaborate, and if all partners are able to agree on a clear division of labor, and an efficient process for making decisions. Finally, outsourcing development to a third party means that the airport can concentrate on its core business, while collecting a fairly predictable monthly income. That allows you to keep your landside investments low—but do keep in mind that the total income will be lower, too. The main disadvantage to this approach is that you lose control over the development process, and you give up some control over the airport’s image. If developers build something super ugly, or if property managers fail to keep their tenants happy, it will reflect poorly on the airport as a whole.

That brings us to an important topic: quality control. When future tenants look out the window of their airport office building, what will they see? A view of dingy warehouses and highway off-ramps, seen through a glass panel that rarely gets cleaned, is unlikely to commandeer high rents. On the other hand, if the office overlooks a park where staff can go for a walk, or if it’s next to an attractive plaza where business owners can take clients out to lunch, then the commercial development will have no trouble attracting tenants.

That people-focused approach sounds great in theory—but how do you actually implement it in practice? The case of Amsterdam offers some clues. When Schiphol Real Estate started to plan a new landside business district, dubbed Schiphol CBD, they focused on what the neighborhood would look like from the perspective of an adult human being, standing about 1.7 meters above ground level. That approach makes sense: while a lot of project renderings emphasize a bird’s-eye view, what the area looks and feels like on the ground is much more important than how it appears from above. A simple point—but one that a lot of airports tend to forget.

With the user’s perspective as the key design guideline, Schiphol then focused on the needs and desires of the people who would be working in the future CBD. To do that, they planned a wide range of services and amenities, including a gym, restaurants, a grocery store, convenient local transport, and a 24-hour childcare facility. They also designed high-quality public spaces between the buildings, featuring outdoor seating, food trucks, and an area for recreational events and after-work parties.

Building a jogging trail or a fancy coffee shop might not sound like an especially lucrative endeavor. But taken together, these types of amenities create an extremely attractive business environment: a place where talented professionals, and the companies that employ them, want to be. The results are readily apparent at Schiphol. Office buildings at the airport enjoy one of the highest occupancy rates in the country, and one of the highest rates of tenant retention: making them a highly profitable source of non-aeronautical income.

The takeaway? Each airport has to decide what’s the best fit for its real estate development strategy: whether it makes sense to develop expertise in-house, to approach partners with a proven track record, or to buy the necessary know-how on a case-by-case basis. Regardless of which model you choose, the essential ingredient for any successful airport real estate venture is partnerships: partnerships that fill in the airport’s own gaps in knowledge and experience, and partnerships that are crucial for getting the project off the ground. It’s also important to approach potential collaborators early in the development process in order to build support for the project’s overall goals. You might be planning the most beautiful shopping center in the world, or a fantastic tourist attraction—but that won’t matter much if the project is based on an outdated retail concept, or if you fail to secure the necessary planning permissions from local authorities. As with many things in life, collaboration is key.